|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

An

Approach To Environment, Ecology & Wildlife |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The

media often reports that all over the industrialized |

|

|

world,

the environmental movement is facing a backlash. |

| |

Major

environmental organizations like Greenpeace and |

| |

the

Sierra Club report that fewer people are joining them |

| |

now.

It is as if people have had their fill of protesting |

| |

against

the latest form of environmental degradation |

| |

and

are looking for some positive developments instead. |

| |

In

the US in particular, with the economy prospering at |

| |

the

moment, the sentiment is in favour of boosting |

| |

further

growth to protect jobs, if not to create them. |

| |

|

| |

In

India too, the media, all too anxious to take its cue |

| |

from

the West, has adopted a somewhat similar attitude |

| |

towards

the environment. It would be hard to find a |

| |

single

environment correspondent in any newspaper, as |

| |

there

was a couple of decades ago. In the ’80’s and the |

| |

’90’s,

especially after the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992, |

| |

the

environment became a political issue with treaties |

| |

being

placed on the international agenda, and the media |

| |

covered

these issues in detail. Now the media believes it |

| |

is

taking a “pragmatic” position on the environment and |

| |

is

not bending over backwards to be green. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

home |

|

|

| prologue |

|

|

| welcome |

|

|

|

contents |

|

|

| subject

moderators |

|

|

|

history |

|

|

| sexuality |

|

|

| social

landscapes |

|

|

| art |

|

|

|

dance |

|

|

| literature

|

|

|

| music |

|

|

| cinema |

|

|

| environment

|

|

|

|

economics |

|

|

|

pot pourri |

|

|

| feedback |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

However,

in both North and South, the media appears to be somewhat off the mark.

Although |

|

|

|

there

may not be the same fervor on the part of the public to take part in demonstrations,

there |

| |

|

is no doubt that they feel strongly about protecting the environment. The

best proof of this are |

| |

|

the regular global surveys conducted by a opinion poll agency in Canada,

which monitors public |

| |

|

perceptions on environmental issues throughout the world. Repeatedly, environment

figures |

| |

|

among the top five, and often three, concerns globally, irrespectiveof the

economic status of |

| |

|

the country. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| How does one

reconcile this with the media perception? |

|

|

| All too often,

both politicians and the media are not in |

|

|

| touch with what

really concerns people. There is no |

|

| question that

increasingly, people everywhere are not |

|

| action too.

Even in a

city like Mumbai, which

is poised |

|

| to become

the most populous in

the world by 2020, |

|

| citizens in

many localities are banding

together to |

|

| protect their

mangroves from being destroyed,

|

|

| clearing their

garbage and the like. A slogan in this |

|

| metropolis

is: “If the mangroves go, man goes too!” |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

Children

in particular have got the message and far more sensitive to their environment

than |

| |

|

|

their

parents. This column will look at various aspects of India's environment,

including its |

| |

|

|

dwindling

wildlife, and keep you abreast of developments in this country. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

EXHUMING

THE GHOSTS OF SILENT VALLEY |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Some 16 years ago,

this columnist wrote a book titled |

|

| Temples or Tombs: Industry

versus Environment, |

|

| Three Controversies,

which was published by the |

|

| Centre for Science

& Environment in New Delhi. |

|

| By far the most interesting

of the three case studies |

|

| was the Silent Valley

hydroelectric project in Kerala, |

|

| largely because of

the high level of consciousness |

|

| among the people in

the state. I had, at the time, |

|

| surveyed similar controversies

around the world, which |

|

| typically revolve around

the claims of the project |

|

| authorities, who exaggerate

the benefits that such |

|

| so-called development

schemes generate, versus those |

|

| of the greens who want

to preserve sites. Nowhere else |

|

| had a project stirred

such strong sentiments on both |

|

| sides. The title of

my book was derived from Pandit |

|

| Nehru's oft-quoted

remark about such projects being |

|

| “the temples of today”. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The

Kerala government's recent announcement that it was exploring the possibility

of re-opening |

| |

|

|

the

Silent Valley will exhume ghosts that most thought had long been interred.

The scheme to

dam |

| |

|

|

the

Kunthipuzha river and generate 120 megawatts of power had raised a

fierce debate in the late |

| |

|

|

1970’s

and is probably the first test case in the country of the supposed

conflict between the needs |

| |

|

|

of

development and environment. Thanks mainly to Mrs

Indira Gandhi, the issue was

resolved in |

| |

|

|

favor

of the environmentalists, who wanted to preserve this rain forest in the

western ghats. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Kerala,

till today, presents a classic paradox in that |

| |

it

is, in terms of human resource development, the |

| |

leading

state in the country with near-total literacy |

| |

and

very low infant mortality and other indices. |

| |

However,

when it comes to economic development |

| |

or,

more particularly, industrial growth, its record |

| |

has

been abysmal. Due partly to its rampant |

| |

unionis

mand high wage rates, entrepreneurs

have |

| |

thought

thrice before investing in the state. The |

| |

result

has been widespread unemployment,

with all |

| |

the

disaffection that this generates. When the

Silent |

| |

|

Valley

project was proposed in the 1970s, the |

|

|

proponents

argued that Kerala lacked industry at |

| |

least

partly because it was short of power. Because |

| |

the

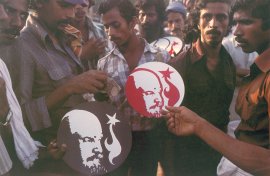

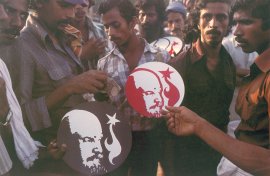

state was heavily influenced by Marxist doctrine |

| |

it

was, after all, the first to elect a

communist party |

| |

to

power by the ballot in the world, as far back as in |

| |

1957

the politicos quoted

Lenin who famously |

| |

declared that soviets (collectivised

farms) plus |

| |

electrification

equalled communism! They argued, |

| |

further,

that this was a renewable source of power, |

| |

unlike

nuclear or thermal energy, and the river was |

| |

otherwise

flowing “wastefully” to the Arabian Sea. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

It

was a group of science teachers and other progressive professionals who

had banded together |

| |

|

|

under

the banner of the Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishat (KSSP) who decided to take

a close look at |

| |

|

|

the

pros and cons of the project. As the name of the organisation suggests,

it first translated |

| |

|

|

scientific

books into Malayalam but then began engaging in debates about environment

and |

| |

|

|

development.

Today the KSSP is one of the foremost environmental groups in the world,

with |

| |

|

|

over 50,000 members. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

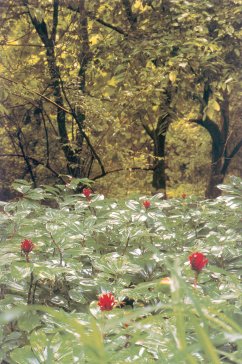

The

KSSP correctly assessed that the economic and ecological value of preserving

this unique strip |

|

|

|

of

forest, which was uninhabited even by tribals, outweighed the benefits of

the power that it |

| |

|

would

produce. It possessed many types of wild flora and fauna, including a

very rare primate, |

| |

|

the

lion-tailed macaque, the loss of which would deprive Kerala of its biodiversity.

As can well be |

| |

|

imagined,

many of the arguments in favor of such preservation, which

have today become |

| |

|

commonplace,

were difficult to defend three decades ago. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Pointedly,

the Kerala State Electricity Board asked: |

| |

|

“Are

monkeys more important than men?” |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Ultimately,

Mrs. Gandhi was persuaded more by the opinion of global environmental organizations |

| |

|

|

like

the World Wildlife Fund and the International Union for Conservation of

Nature to call off the |

| |

|

|

project.

She was always more susceptible to pressure from abroad than

from within the country, |

| |

|

|

which

is why, for instance, she decided to hold elections to legitimize

her authoritarian rule during |

| |

|

|

the

emergency in 1977. When she returned to power

in 1980, she instituted a committee under |

| |

|

|

Prof

M.G.K. Menon, which ruled against the

project and she went along with it. Subsequently, Silent |

| |

|

|

Valley

was declared a national park, which is its status till today. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

This

legal position cannot be easily changed. As witnessed in state after state,

attempts by politicians |

| |

|

and

industrialists to dereserve national parks have not been favourably received

by courts. How the |

| |

|

Kerala

government ever hoped to get around this reservation is a matter of considerable

speculation. |

| |

|

According

to newspaper reports, the Union Environment Ministry had issued a directive,

suggesting |

| |

|

that the state government obtain clearance from the Indian Board of Wildlife,

as well as the Supreme |

| |

|

Court.

The former is bound to put its foot down, for Silent Valley is one of the

last vestiges of what is |

| |

|

known as shola forest the unique ecosystem sheltered in the folds of the

western ghats. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Since these areas of the

western ghats are internationally recognised as one of the “hot spots”

for |

| |

|

|

biodiversity in the globe,

Silent Valley is in far greater need of protection than the

temperate zones |

| |

|

|

of the Himalayas in north

India. It is also understood that the Kerala forest

department itself will |

| |

|

|

oppose the project. For

all these reasons, the State Electricity Minister,

K. Sivadasan, who had earlier |

| |

|

|

dismissed environmentalists'

fears as “imaginary”, to be backtracking on the move. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

It is strange that the many politicians

and bureaucrats have failed to learn the lessons of history.

The |

|

|

|

Silent

Valley issue raised a fierce controversy, not only in Kerala but elsewhere

in the country notably |

| |

|

in

Mumbai and Delhi and internationally. As the Menon committee report

pointed out, it was better

to |

| |

|

err

on the side of caution and prevent some of the country's

most valuable natural heritage

from being |

| |

|

lost

to future generations. What is more,

if there was an economic cost to be

put to such preservation, |

| |

|

it

was the presence of priceless

plants such as the wild varieties of rice

available in the area (and

in |

| |

|

the

forests of Sri Lanka). These

contain genes which can resist pests which attack new high-yielding |

| |

|

varieties

of rice, and are therefore like a natural storehouse whose economic benefit

is simply |

| |

|

incalculable. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

No

one can deny that Kerala needs power, but there are several alternatives

which need to be explored. |

| |

|

Unfortunately,

the state government, which has perhaps never recovered from the

slight at the hands |

| |

|

|

of

the Centre in preventing it from exploiting what it believes are its own

natural resources, has been |

| |

|

|

turning

to other ill-conceived energy schemes. These include

another hydroelectric project

in a western |

| |

|

|

ghats

forest, an offshore thermal plant and

even a nuclear station in one

of the most densely populated |

| |

|

|

states

in the country. Instead, it

could consider small run of the

river hydel units along its 43

rivers, |

| |

|

|

which

would generate sufficient power for small agro-industrial units that are

in any case the mainstay |

| |

|

|

of

Kerala's economy. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| In

the final analysis, the attempt to resuscitate |

|

|

| the

long-buried Silent Valley project raises, as it |

|

| did

three decades ago, vital questions concerning |

|

| the

development paradigm which the state intends |

|

| to

adopt. If big industry has been deterred from |

|

| entering

the state for reasons already stated, the |

|

| government

ought to consider how to promote a |

|

| more

localised form of development where the |

|

| abundant

natural resources are exploited in a |

|

| more

ecologically sensitive manner. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Love, |

| |

|

Darryl |

| |

|

|

|

TOP |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()