|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

THE IDEA OF INDIA |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

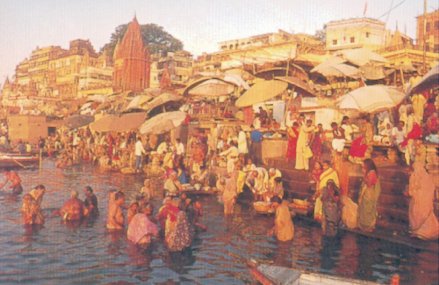

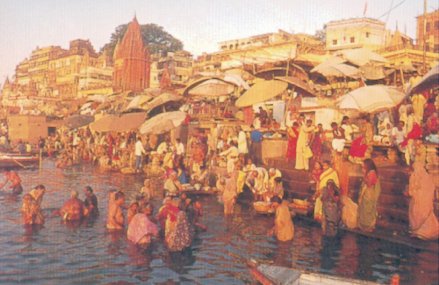

India, many believe, is an idea. It is not one territory, not one people but a melting pot in |

|

| |

|

which many cultures have mingled to produce a unique sensibility, a grand civilization. |

|

| |

|

The

whole that is now India is greater than the many parts that have gone into its making. |

|

| |

|

Inevitably India means different things to different peoples. It denotes at the same time |

|

| |

|

spirituality and science, art and religion, antiquity and development, myth and history. |

|

| |

|

The

rich variety of its natural landscape, colors, textures, food and peoples has appealed |

|

| |

|

to the

romantic imagination of the civilized world since ancient times. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Change and Continuity |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In the nineteenth century, India came to be imagined as part of a mysterious orient |

|

| |

|

|

imbued with an ancient wisdom timeless and changeless. Nothing could be further from |

|

| |

|

|

the truth. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

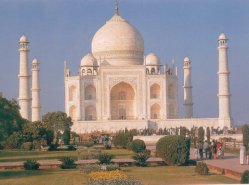

| India has always been steadily changing,

internally |

|

|

| and in step with the rest of the world. Between the |

|

| Vedic Age and the Classical Gupta Age, Indian state |

|

| and society underwent stages of transformation. |

|

| People came - especially from the North-West - in |

|

| a

steady stream bringing with them new crafts, skills, |

|

| languages and practices. The Turkish and other |

|

| Central Asian tribes brought with them Islam and |

|

| many innovations in social and political institutions. |

|

| The

flowering of Indian Muslim civilization under the |

|

| four great Mughals marked an epoch of continuous |

|

| development. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| home |

|

|

|

| prologue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

welcome |

|

|

Nearer our own time, and better understood by us, the colonial and post-colonial states |

|

| contents |

|

|

have created new boundaries and institutions which have profoundly altered the lives of |

|

|

subject

moderators |

|

|

all segments of Indian peoples. |

|

| history |

|

|

|

|

|

| sexuality |

|

|

Much of India’s ‘ancient’ wisdom was not so ancient as might be believed. ‘Hinduism’ is |

|

| social

landscapes |

|

|

supposed to be ( one of ) the oldest religions of the world. But much of its known |

|

|

art |

|

|

features are less old than Christianity or Islam. The first surviving Hindu stone temple was |

|

| dance |

|

|

built only 500 years after the Athenian Acropolis. Popular deities like

Rama, Ganesha or |

|

| literature

|

|

|

Hanuman are much younger than Christ. |

|

| music |

|

|

|

|

|

| cinema |

|

|

|

|

|

| environment |

|

|

|

|

| economics |

|

|

|

|

| pot pourri |

|

|

|

|

| feedback |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Between the time of the early Greek philosophers and St. Thomas Aquinas, Buddhism arose |

|

| |

|

as a great religious movement, altered the course of India's history, declined and finally |

|

| |

|

sank back into the Hinduism from which it had emerged. In he meanwhile, however, |

|

| |

|

Buddhist ideas spread over virtually half the vast Asian continent. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

And yet India's antiquity compels our imagination. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

First, because it is old. The sacred bull and the holy pipal tree have been around for 4,500 |

|

| |

|

years. The hymns of Rig Veda are older than the oldest verses of the Old Testament. Second, |

|

| |

|

Indian culture has been always and fully conscious its own antiquity. It goes further, it |

|

| |

|

exaggerates its antiquity, upholds it as a virtue and claims its unchanging traditions as its |

|

| |

|

greatest achievement. Indeed, India's claim to singularity may well lie in having the longest |

|

| |

|

cultural continuity anywhere in the world. None of India's ancient civilizations were ever |

|

| |

|

completely destroyed or forgotten. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The Glory of India |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The unembarrassed admiration of one of the greatest historians of Ancient India, |

|

| |

|

|

A. L. Basham, is directed towards India's tradition of humanity and it's people's passions. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The vast geographical and political spread of India has been, inevitably, torn by internecine |

|

| |

|

war, pulled asunder by the unscrupulous cunning of rulers and statesmen, ravaged by |

|

| |

|

famine, flood and plague. Judged, however, by the standard of other ancient cultures, India's |

|

| |

|

social and political ideals were lofty, fair and humane. War did not lead to mass civilian |

|

| |

|

slaughter, punishment rarely descended to sadism, slaves were few and heir rights were |

|

| |

|

protected. In the ancient world, India was an unusual example of a humanitarian order. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Indian association with fatalism and asceticism is misleading. Even in the ancient days, |

|

| |

|

Indians lived within complex and evolving societies, achieving great heights in the sciences, |

|

| |

|

philosophy and art. Nature's plenty gave prosperity but did not induce lethargy. India was a |

|

| |

|

|

cheerful land with a robust enjoyment of simple pleasures. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Class and Caste - A Difficult Legacy |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Is India's ancient glory unalloyed by iniquity? To most social |

|

|

| scientists and many modern Indians, the most troubling legacy |

|

| of Ancient India is the caste-system. It has frozen Indian society |

|

| in an unchanging hierarchy, legitimating oppression and social |

|

| exclusion. It has helped to entrench the maxim that men's and |

|

| women's destinies are determined by their birth into a particular |

|

| social order. But what is caste? Why is it so powerful and enduring ? |

|

| |

|

| The term 'caste' is not Indian. The Portuguese who came to India |

|

| in the 16th century used the word castas (meaning tribes, clans or |

|

| families) to denote the many divisions with Hindu society. The |

|

| word stuck and caused (continues to cause) many a gray hair on |

|

| the scholar’s head. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The term 'caste' comprises two quite different institutions of Hindu society - varna (class)

|

|

| |

|

and

jati (literally birth group, caste, for want of a better word). |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Varna |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

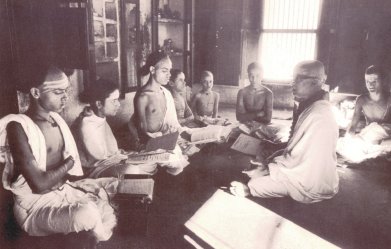

Varna refers to the four-fold classification of society expounded during the Vedic period. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

How did the four classes come into being?

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Here's what the myths say.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In the later Rig Vedic Period, we encounter the Hymn of the Primeval Man that seeks to

|

|

| |

|

|

explain the Foundation of the Universe.

Prajapati- the Primeval Man (Purusa) - committed

|

|

| |

|

|

his body to the first cosmic sacrifice. From his body the universe was produced.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

The brahman was his mouth

|

| |

|

| |

Of his arms was made the warrior |

| |

|

| |

His thighs became the vaisya

|

| |

|

| |

Of his feet the

sudra was born.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

These were the four

varnas. Brahman ( priest ), Kshatriya ( warrior ), Vaisya ( traders ), and

|

|

| |

|

|

Sudras ( cultivators ). There are never more or less than four and their order of precedence

|

|

| |

|

|

has not changed in 2,000 years.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Varna literally means

colour. Brahmans wear white, kshatriyas yellow, vaisyas red and

|

|

| |

|

|

sudras black. The order of precedence is ritually legitimated by the degree of pollution

|

|

| |

|

|

attached to being born into one or another of them. The least polluted were the brahmans

|

|

| |

|

|

and the most polluted were the

sudras.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

How would a historian explain the four fold varna system?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The very mention (mythic or otherwise) of the four varnas in the Rig Veda indicate their

|

|

| |

|

antiquity. The system must have already been there about 1000 B.C.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| The Aryans were a pastoral people. Cattle-keeping and

|

|

|

| cattle-wealth marked the highest ranking and the ruling

|

|

| clans were called rajanya, who later adopted the title

|

|

| kshatriya (kshatra meaning power). But as the Aryans

|

|

| moved into the fertile and productive Ganga Valley, they

|

|

| and the non - Aryans already settled in these areas (vis)

|

|

| began to value land as the major source of wealth. The

|

|

| Aryan ruling class looked upon the brahman (priest) to

|

|

| confer legitimacy and convert them into KINGS (rajas)

|

|

| through powerful sacrifices. In return, the rajas paid

|

|

| fees

and gifts to the priests. Together, the priest and

|

|

| the king

( as in many other ancient polities

) constituted

|

|

| the elite of society. |

|

|

|

| Those called vis adopted the title vaisya and were the

|

|

| leading households of farmers, herdsmen or merchants.

|

|

| The heads of the household were called grihapati and

|

|

| they paid tribute to the kings and the priests.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Subjects of the raja

(praja, to start with) and servants of the elite were divided into sudras

|

|

| |

|

|

and

dasas. These may have been non - Aryans or war captives. They were usually set to work

|

|

| |

|

|

the land and tend the cattle. Even lower in rank were the 'untouchables' so called because

|

|

| |

|

|

their occupations were supposed to be deeply polluting - leather workers, corpse handlers,

etc.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Jati

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Jati is not fixed. There are thousands of jatis in different parts of the country. Jatis rise and

|

|

| |

|

|

fall in social scale, they die out and new ones emerge.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Ancient texts refer more to varna than to

jati. But when jati is mentioned, it does not imply

|

|

| |

|

|

the rigid and exclusive social groups of later times.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The first clear mention of jati is in Manu's

Lawbook, the Dharmashastra. He uses the term to

|

|

| |

|

|

describe proliferating lower occupational groups, which (according to Manu) consisted of

|

|

|

|

|

descendants of illicit marriages of various kinds among the original

varnas.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Manu's explanation of the emergence of jatis through intermarriage and intermingling of the

|

|

| |

|

four varnas was accepted for a long time and by a surprising number of scholars. It is now

|

|

| |

|

recognized that such a trajectory of development is unlikely, if not impossible. Indeed,

|

|

| |

|

despite many overlaps, varna and jati have never quite harmonized.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The development of jatis - as a system of groups within the varna system - normally

|

|

| |

|

|

endogamous, commensal and craft-exclusive must have taken thousands of years. Such a

|

|

|

|

|

system of social ranking emerged from the association of many different racial and other

|

|

| |

|

groups in a single cultural system.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The caste group emerged as the center of focus for corporate feeling. Probably a result of

|

|

| |

|

intertwining tribal affiliation and professional association. The introduction of new racial

|

|

| |

|

groups and the development of new crafts continually elaborated both.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The corporate sense of caste emerged from the time when small clans living in isolated

|

|

| |

|

villages sought to hold themselves aloof by a complex system of taboos. As these small and

|

|

| |

|

primitive people were forced to come to terms with an increasingly complex social and

|

|

| |

|

economic system, they sought to group themselves around existing corporate identities.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The system began to elaborate and grow rigid in the Middle Ages.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The Europeans encountering a system they imperfectly understood, exoticised or demonised

|

|

| |

|

|

'caste' where fancy (or self-interest) led. Among the many drastic interventions of the British

|

|

| |

|

|

Indian State, a damaging one was to attempt a taxonomy of castes based on the mistaken

|

|

| |

|

|

assumption that

jatis, like varnas, are immutable. They assumed - completely mistakenly -

|

|

| |

|

|

that caste pertained to the ritual rather than the social and historical. This was a costly

|

|

| |

|

|

mistake.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The term 'caste' lost most of its historic political, social, economic and cultural attributes in

|

|

| |

|

|

the course of the twentieth century. And yet, it continued to attach corporate loyalty. On the

|

|

| |

|

|

one hand, 'caste' became a platform for preserving old and voicing new entitlements; on the

|

|

| |

|

|

other, its emptiness opened it up to manipulation by conflicting groups and classes.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

We shall see how many other social relations that developed in ancient India cast their long

|

|

| |

|

|

shadow - sometimes drastically altered, sometimes only marginally modified - across

|

|

| |

|

|

several millennia of political and social development. In the next few meetings we shall

|

|

| |

|

|

discuss themes and episodes from between the events associated with the great epic,

|

|

| |

|

|

Mahabharata (900 BC) to the close of the Classical Gupta Age (500 AD).

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Love, Samita |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

TOP

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()